The Society for Neuroscience hosted a live webinar on How to Prepare for, Defend Against, and Recover from Animal Rights Oppositional Efforts, which included moderator and Chair of SfN’s Animals in Research Committee Katalin Gothard, MD, PhD and panelists Eric Nestler, MD, PhD, Sharon Juliano, PhD, and Matthew Bailey, President of the National Association for Biomedical Research (NABR) and the Foundation for Biomedical Research (FBR).

Both scientists were victims of oppositional efforts from animal rights groups, and they shared how their work, reputation and at times, their lives, were threatened by these groups, and the steps that they and their institutions took to combat the efforts.

Nestler’s lab at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai specializes in addiction and depression research, working with rats or mice to better understand the mechanisms of the two disorders in the brain. Five years ago, he was targeted by PETA. Nestler started to receive countless hateful letters and threatening emails, such as “What you do to mice should be done to you,” his work was reported falsely in PETA’s magazine, and PETA even made a YouTube video that implied Nestler was experimenting on women.

These attacks continued until about two years ago – they stopped with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Unlike many other scientists who are targeted by animal rights groups, Nestler said, he was fortunate to have the full support of his institution when his work and reputation came under fire. Nestler also had the support of SfN and America College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Sharon Juliano specializes in trauma-related research at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. She shared a picture of a flyer posted in her neighborhood reading, “Sharon Juliano, Wanted for Murder, for Cruelty, for Deceit, for Crimes Against Animals.”

The sign was made by an animal rights group, and for three years, group members showed up outside of her house and institution, and even staged walks around the neighborhood as “animal ghosts.”

Like Nestler, Juliano relied on support from her department, NABR/FBR, and other scientific organizations to combat the relentless threats, vandalizing, and hate notices she received.

For scientists who may find themselves in similar situations, Juliano stated the most important thing is to be prepared, which includes coordinating with and involving your institution, and determining a spokesperson. This should be someone who knows your work and is willing to speak on your research and your behalf.

Matthew Bailey addressed the question many scientists who find themselves in this position ask – why me?

Bailey assured it is not personal if your work with animals comes under attack, but instead a part of the larger goal of animal rights groups – fundraising. Disrupting animal research means big money for these organizations.

For example, the People for Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), and the PETA Foundation, also known as the Foundation to Protect Animals, estimated a total revenue of $82 million in 2020 alone.

A large part of the problem, according to Bailey, is public policy measures that threaten animals in research, due to ignorance and misinformation about research and animal testing. Bailey urged scientists to routinely reach out to local legislators about the importance of the work they are doing, noting they can do so using electronic services provided by SfN’s Advocacy Action Center and other organizations who offer similar services.

Simply inviting your local lawmakers for a tour of your lab may lead to better understanding of your work and its importance, potentially influencing future legislation.

All panelists urged scientists to be open with the public about their research, as the panelists agreed a large part of the negative stigma regarding animals in research is a lack of public knowledge or education. Everyone should work with their academic institutions to emphasize the importance of work on laboratory animals any time a press release or related update is issued that highlights a significant research advance.

When being targeted, Bailey urges scientists to respond to the public, rather than the animal rights groups, and share positive news about the benefits of your research, emphasizing the connection between human and animal health.

Even at the graduate student level, there are ways to get involved in advocating for animals in research. Bailey encouraged graduate students to start small, providing family and friends context about the research you are working on.

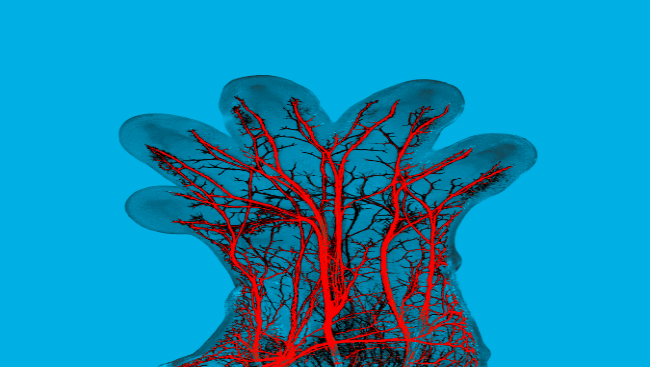

The panel concluded by stating a widely known fact: animals in research are an essential part of understanding how the brain and entire neuronal systems interact and generate subjective experiences and complex behaviors; current alternatives like computer models or cell cultures are no substitute for a whole organism. Virtually every major advance in medicine has relied upon the use of animals in research.

Therefore, scientists need to be prepared, formulating an action plan with their institution or associations, informing the public and lawmakers of the necessity and key benefits of animals in research for cures, treatment, and medication for human ailments. Researchers should be empowered and not afraid to defend their work fiercely when an attack from animal rights groups inevitably comes.

The panelists encouraged all scientists to complete these action items:

- Set a crisis management team – who can you reach out to at your institution? What players should be involved?

- Share your research, and use of animal models with your members of Congress.

- Provide public education on your research – teach others about your work, and promote locally – public schools, etc.

- Have a prepared elevator speech ready – where you can explain your research and the value and necessity of animal models.

- Open your lab to tours to ensure the research is open and available to those who are curious.

Want to learn more or discuss this topic? Explore the Neuronline Community for more resources.