Ways to Change the Implicit Bias Status Quo

- Featured in:

- Increasing Women in Neuroscience

We're working on improvements. Stay tuned for updated content.

These findings underscore the continued impact of implicit bias — the often-subtle discrimination based on cultural stereotypes — on evaluation of women and why it needs to be addressed. But what can actually be done? Anne Etgen, neuroscientist and professor emerita at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, comments on measures that can be taken in the neuroscience field.

What do the data show about the representation of women and underrepresented minorities in neuroscience?

In the 2014 NSF survey of doctorate recipients from U.S. universities, if you look at total earned doctorates in neuroscience and neurobiology awarded to United States citizens and permanent residents, there's a very high percentage of females — more than 50 percent. This has been true for decades. But, that is not translated into comparable representation of women in academic tenure track positions within the neurosciences in the United States.

There's a very small fall-off at the transition from graduate student to postdoc, but a much greater fall-off of women and of underrepresented minorities from postdoc to tenure track faculty position and from assistant professor to associate professor to full professor.

Additionally, in the NSF data, out of 801 PhDs awarded in 2014, only 29 went to blacks or African Americans, 53 to Hispanics or Latinos, and one to an American Indian or Alaskan native. This sum is less than the number awarded to Asian students who are United States citizens and permanent residents. We're not doing a good job of getting underrepresented minorities nationwide into the field. They're certainly nowhere near their proportional representation in the United States population.

How does implicit bias factor into women and underrepresented minorities dropping out of academia as they advance?

Data disprove traditional thought patterns about why women drop out — concerns that they are not hired or promoted because if they have families, they are not as productive. If you look at the productivity, promotion rates, publication rates, and grant rates for women in tenure-track positions who do and don't have children, there is simply no evidence that women who have children fall behind their colleagues who don't.

The question is, what is going on? Implicit bias is a big part of the answer.

Women and minorities are evaluated differently. Data, such as the 2012 Moss-Rascusin study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), show that there is still implicit bias against women when evaluating resumes, competence, providing mentoring opportunities, and salaries. Women are also less likely to be nominated for prestigious awards.

There are also data suggesting that if women and underrepresented minorities see a job description which is very specific, they will self-eliminate and not apply whereas men will still apply.

A 2014 study in PNAS shows that in labs of (what this article defined as) elite investigators who were male, there were significantly fewer women postdocs than in labs of individuals who were PIs of non-elite labs and in labs of women PIs who were considered elite investigators. In “feeder” laboratories headed by males, defined as prominent laboratories that produce a high percentage of the individuals recruited to junior faculty positions, there is a reduced percentage of women in the pool. Therefore, there is a reduced pool from which women are likely to be recruited.

Evaluation bias by students against women and minority professors is part of the picture, too. There is still gender and racial bias in how students evaluate their instructors. This can handicap women and minorities during the promotion process.

Is it possible to curb the effects of implicit bias? If so, what strategies can help?

Yes. For progress to be made, people have to recognize implicit bias in themselves. The Harvard implicit bias test data show that bias against women as scientists is equally shared by men and women. The bias against minorities in science is equally shared by whites and minorities. Once we recognize the existence of implicit bias, we then have to implement practices that can mitigate its effects.

Diversity of search committee composition is important. In addition, data show that using open job descriptions (i.e., broadly rather than narrowly defined research area) markedly improves the quantity and quality of candidates in the applicant pool and brings more gender and ethnic diversity to the applicant pool.

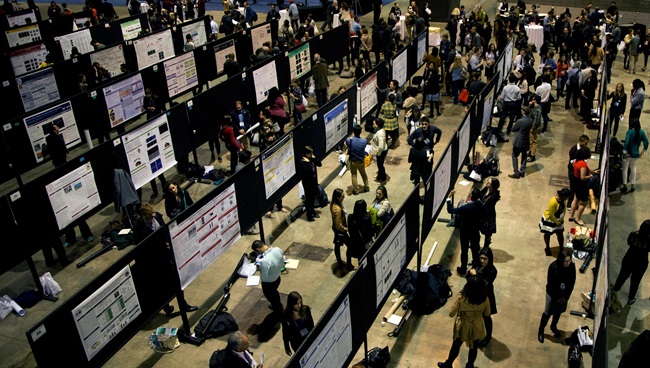

Institutions should actively reach out to people and invite them to apply. For example, members of the institution can look for viable candidates at scientific conferences and other venues, keep them in mind for future positions, and invite them to apply.

When getting ready for a junior faculty job search, institutions should attend diversity events hosted by the Society for Neuroscience. One can also contact leaders of NINDS-funded national programs to mentor diverse early career neuroscientists, such as the University of Washington program called BRAINS, to identify diverse candidates and consider inviting them to apply.

Be proactive in nominating and sponsoring women and underrepresented minorities for awards and honors, and as seminar speakers and peer reviewers. This puts them in the national limelight and is important for their career development. Currently, women are not nominated for major research awards in numbers proportionate to their representation in the field.

For faculty and department heads working to reduce implicit bias in evaluations, recruitment, retention, and other institutional processes, what tools do you recommend they use?

Explore the IWiN Toolkit: Implicit Bias, and the IWiN Toolkit: Candidate Recruitment and Evaluation. During recruitment, the toolkit provides good guidelines about scientifically studied, evaluated, and published strategies that reduce implicit and evaluation bias and increase the likelihood that you're going to hire women and minority faculty.

These individuals need to be evaluated on the strength of their science and the contributions they can make to the institution, and not be made to feel that they are being considered only because the institution is trying to become diverse.

The toolkit provides a list of questions that should not be asked, and a form which each institution or search committee can tailor to its own purposes for evaluation. This can help make sure candidates are evaluated by specific criteria, not an email to the search committee chair that says, "I didn't like that person." That's not an acceptable contribution to an evaluation process.

*Interview edited for length and clarity.

For more information on these topics, visit the IWiN Toolkit: Implicit Bias and IWiN Toolkit: Candidate Recruitment and Evaluation.

Speaker