Overcoming Challenges as a Native American in STEM

Naomi Lee is an assistant professor in the department of chemistry and biochemistry at Northern Arizona University. Lee's research focuses on infectious and chronic diseases while using chemistry and biology tools and public health research to inform vaccine design. In this interview, Lee discusses challenges of being a Native American in research, and her goals of improving American Indian and Alaskan Native health through research, STEM education, and mentoring.

Could you talk a little bit about growing up on a reservation?

I grew up on the Seneca-Cattaraugus Reservation in western New York. We didn't leave the area too much, so I didn't know a lot about what was out there.

I didn't realize I was different according to the norm, because I was surrounded by people who were like me. Everyone faced a lot of the same challenges.

It wasn't until I went to undergrad that I realized I was different.

What made you pursue a career in science?

I participated in a program called Science and Technology Entry Program (STEP) on my reservation. It was my first real exposure to collecting data and doing experiments.

In undergrad, I had a mentor, Dr. Jason Younker, who was one of the first Natives I met with a PhD. He encouraged me to seek research opportunities.

I did a summer program at the University of Southern Mississippi, and I decided that research was what I wanted to do.

During my first post-doctoral training at the National Institutes of Health I was able to start looking at issues affecting Native American communities and working with Native American students. At that time, I realized many of the health disparities you see among tribal communities are social-behavioral-related health issues as well.

At the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), I was exposed to viral immunology and infectious diseases. That piqued my interest in designing vaccines.

My training opportunities have led me down to this path where I'm able to merge my basic science training with interest in public health and my communities. My main focus is using what we refer to as an "indigenous lens" to look at health questions. I ask myself, "How can I apply indigenous knowledge and perspective to drive research that will improve my communities?"

What has been the most profound challenge you've faced?

When I was accepted to Rochester Institute of Technology I told my high school teacher that I was going to study biochemistry. The words I remember are, "Oh, that's really hard. I'm not sure if you're going to make it."

At first, I was young, and I was like, "What are you talking about?" And now I'm like, "Take that."

That was probably the first time I really remember being discouraged from science.

Throughout my undergraduate and graduate career, there have been a lot of microaggressions and racism. However, not so much since my post-doc.

What helped you overcome those challenges?

I'm Seneca and as a graduate student I was introduced to Dr. Clif Poodry, who is also Seneca. He introduced me to the NIH and Dr. Rita Devine at NINDS. He was instrumental in my early post-doctoral training, along with Dr. Devine, who's still a huge support system for me.

These mentors helped me realize you don't have to have separate identities. Whatever identities you have, they can come together in your work environment.

I struggled with managing my cultural identity and my identity as a scientist. Now I take pride in all of my identities. I don't keep them separate. Everybody knows who I am. That the fact that I am Native American, it makes me unique and is a strength, not a weakness.

Over the years, I've really learned to appreciate all the individuals who supported me and allowed me to express all my identities.

What challenges do you see Native students facing today?;

I still see issues, even with the high school students, that I faced as a student, where they're not being encouraged to aim high.

They're being encouraged to apply to trade jobs, or community college, which I totally support. However, I don't see a lot of students being told to apply to the top universities such as Stanford, Harvard, MIT, etc. They're perfectly capable of succeeding in these universities, but it's much like what I experienced as a student - they're setting the bar low for us, because that's the expectation.

I want to focus on knocking down those obstacles I experienced so the next generation doesn't have to experience them. I know people did that for me as well. We have to continue breaking down barriers that our younger generations are facing.

Native students have to be resilient. They're going to face discouragement and obstacles. Building a network of others that will help support them. No one should do everything on their own.

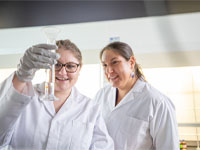

Naomi Lee and Noelle Waltenburg (BS, Chemistry, 2020).

Can you recommend any resources for Native students to build networks or experience research?

NINDS Tribal Health Disparities Program, is great because it exposes more native students to neuroscience. Dr. Rita Devine and her colleague, Dr. Angel de la Cruz Landrau, run the summer internship program.

I'm actively involved with the Society for Advancement of Chicanos and Native Americans in Science (SACNAS). It's a good society for the graduate and professional level. It's also supported by NIH, so they have a lot of biomedical opportunities available.

As an early student, I was introduced to the American Indian Science and Engineering Society (AISES). It was the first time I realized there are many other natives in STEM.

AISES is very supportive, especially for high school and undergraduate students. They are now building their graduate and professional support systems. For example, they have different mentoring programs. However, just attending a conference with people like me, and being able to present my research and not feel judged is rewarding.

Where do you see diversity, inclusion, equity, and equality going over the next five to ten years?

I would like to see more indigenous and traditional knowledge incorporated into STEM and bringing back our values that we had as indigenous people.

We were the original chemists, biologists, neuroscientists of this land. Just thinking about how, as native people, we have a more holistic approach to healing and the use of traditional medicine. I think there's a lot of movement in that area.

The Tribal Health Research Office at NIH hosted a conference on traditional medicine last fall (2019). Scientists could attend and learn more about what native people bring to the field.

I also think if we're really going to change or improve diversity, equity, and inclusion, we need to expose our younger generation at an earlier age to these different ideas. The earlier we expose our younger generations, and the more we incorporate our indigenous knowledge, the more they're going to see themselves as a scientist. Once they start seeing themselves as a scientist, that's when we'll really start to see the change in diversity, and equity, and inclusion.

Speaker